文献詮索:「過去時制=遠隔形」説をさかのぼる:Steel 1975

英語において,過去時制の形式は過去の出来事を表す以外にも,反事実性や丁寧さを表したりする用法をもっています.そこで,これらは何らかの意味での「遠さ」を表すという説が提唱されています.たとえばラネカーの認知文法では,現在時制と過去時制は proximal vs. distal という近さ/遠さの対立が基礎にあると主張されています*1.ラネカーによれば,節の基盤化要素*2は主に法助動詞と時制の2つがあるとされます.前者の法助動詞は非現実の標識であり,この標識の有無は非現実/現実の対立に対応します.一方,後者の時制形式は遠近の対立に対応します.すると,非現実/現実と遠近の対立により4通りの区別がなされることになる,というわけです:

- 法助動詞ナシ+現在時制 : 現実領域における近さ : 現在時

- 法助動詞ナシ+過去時制 : 現実領域における遠さ : 過去時

- 法助動詞アリ+現在時制 : 非現実領域における近さ : 認識上の近さ

- 法助動詞アリ+過去時制 : 非現実領域における遠さ : 認識上の隔たり(e.g. 反事実性)

こうした主張はかなり広く受け入れられています.

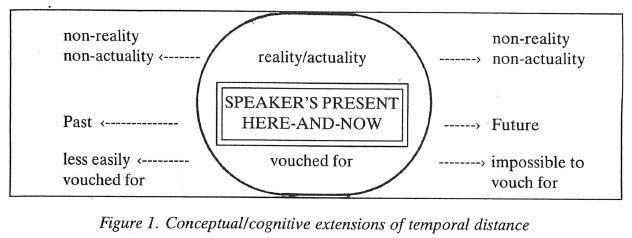

また,これと似た主張として,過去時制が表す時間的な「距離」が一種の概念隠喩として反事実性などに拡張されているのだという説もあります.代表的なものとしては Fleischman (1989) が挙げられます:

Suzanne Fleischman, "Temporal distance: a basic linguistic metaphor," Studies in Language 13-1 (1989):

ここでも「距離」すなわち遠近の対立に基づいて時制の異なる用法を統一的に記述しようという試みがなされています.

こうした説がどのあたりにはじまるものなのか詮索してみますと,どうやら次の文献がごく初期のものと考えられるようです:

Susan Steele, "Past and irrealis: Just what does it all mean?" IJAL, vol. 41, no. 3, July 1975, pp. 200-217.

以下,関連する箇所を抜粋してみます:

The aforementioned grammars often contains statements to the effect that the morpheme which marks past tense also marks irrealis in sentences which describe unreal situations. Consider the following, randomly chosen examples. About Garo, Burling notes, "The rather elusive uses of this suffix [cim] fall mainly into two sets, one to indicate action that is past and done, the other as the coordinate in 'if' sentences."[fn2] In Chipewyan, Li notes that the past tense occurs "... sometimes with the meaning of contrary to fact when used with a conditional clause."[fn.3] Of Old Marathi, Master says, "The past tense is also used as a conditional...."[fn.4] Non-exotic English, too, partakes of the phenomenon. The English morpheme -ed indicates past tense: (1) Mary liked to roll drunks. But -ed can also indicate irrealis. Verbs in the protasis of contrary-to-fact conditionals are inflected with -ed: (2) If John accused Mary of rolling drunks, she would hit him over the head with a sack full of old wine bottles. (John hasn't accused Mary of rolling drunks.) -ed means

attempted but unachieved with verbs which carry some intentive meaning: (3) Mary intended to get married, but she couldn't stand to lose her identity. (Mary didn't get married.)

(pp. 200-1)

Models inflected with -ed indicate not past time but rather a more tenuous possibility.[fn.5] The warning n (4a) is much stronger than that in (4b): (4a) Cigarette smoking may be hazardous to your health. (4b) Cigarette smoking might be hazardous to your health.

(p. 201)

These four languages were randomly chosen, but insofar as each of them exhibits a morpheme which indicates both past time and some notion of irrealis, they are representative of the world's languages. As Hale notes "... it is at least sporadically universal among the world's languages when an element which has the meaning (very approximately) intentive occurs in the past tense, unachieved intention is implied."[fn.6]*3 His statement gives the unfortunate impression that past tense is somehow basic; the arguments of this article will militate against that position. But Hale's suggestion that past tense and irrealis (in his statement expressed as "unachieved intention," a specific sort of irrealis notion) are universally related is important.

(p. 201)

The meaning polite request, a gloss I have ignored up to this point, is the semantic bridge which connects the parallelisms of past and irrealis. We have seen that -ed in English can indicate /past/ and /irrealis/; it can also indicate a very polite request. Compare the following two sentences: (57a) Will you pass the salt. (57b) Would you pass the salt. The effect of the second is to abstract the speaker from the request. I hypothesize then that past and irrealis have in common the semantic primitive

DISSOCIATIVE.[fn.79]*4 Politely to request something is to dissociate oneself from the request. Past time is dissociated from present time. Irrealis is dissociated from reality.

(pp. 216-7)

結び:

Within the framework of a cross-linguistic connection between markers of past and markers of irrealis, this article has argued for the reconstruction, as one element, of two cognate sets, one meaning /emphasized past/ in the protolanguage; the other meaning irrealis. I have argued that past and irrealis are actually modifications along tense-aspectual and modality parameters respectivfely of the semantic primitive DISSOCIATIVE. I have argued this specifically for Uto-Aztecan, but given the cross-linguistic relationship between past and irrealis, I should like to suggest that DISSOCIATIVE is a universal semantic primitive. The Uto-Aztecan reconstruction has, thus, cast some light into what once was a very dark corner of semantics.

*1:eg. FCG2, §6.1

*2:たいていの場合,「グラウンディング要素」などとカナで訳されているようです.

*3:Kenneth Hale, "Papago /či-m/," mimeographed (Cambridge, Mass.: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1969).

*4:Hansjakob Seiler ("Abstract Structures for Moods in Greek," Language 47, no. 1 [1971]: 79-90) suggests the term to describe a connection between the optative and preterit morphemes in Greek.